New Creation Community

A Seventh-day Adventist Experience

When God and Man are in Disagreement

1844 was also an election year...

A number of my young friends are struggling with their Christianity right now, really questioning their beliefs, values, and spiritual life. They not only question the nature of God; they doubt His very existence. It’s hard for them to reconcile the Old and New Testament God, especially when it comes to homosexuality, the sanctity of the Sabbath, seeming contradictions in the Bible and hypocrisies within the church. Like many people, they wonder, how does their faith work in the real world? This election year in particular has buried them in a blizzard of confusion over national divides: Black Lives Matter vs. the police, science vs. faith, fake news vs. legitimate information, socialism vs. capitalism. Words are frequently re-defined, making discussion harder. Even gender is blurry and contentious. What is right? What is good? Who can we trust?

This series of blogs will look at these questions and what the Bible has to say specifically or in principle.

But first, some context! Let’s go back a few years to the founding of Seventh-day Adventism.

It was also an election year in 1844.America was starting to come into its own, flexing muscle as an independent, industrialized nation.

- Technology and communication exploded with the sound of the steam engine and whine of the telegraph wire. Cross-country, even global, news became accessible within minutes.

- Science, in the form of Darwin and Karl Marx did its best, accidentally or intentionally, to erase God.

- We could do more, and we wanted more, we knew ourselves to be more. But our advances and expansionist policies also threatened to boil over into war with Mexico over the southwest territories.

- Factories and crime increased within growing cities.

- Workers’ rights and labor reforms bubbled into our national dialogue, as did the muddy problem of slavery that was snagged within our economy.

- Nationwide, cholera from dirty water, influenza from China, small pox and yellow fever especially ravaged the poor, weak and elderly.

- The worst flood ever recorded burst the Missouri and upper Mississippi that year. Hundreds died from the disease that followed its receding muck.

- A potato blight hit the eastern states--a foreshadow of the greater famine from 1845-47 that would send 5 million Irish to the U.S. alone.

Red-lined

Already in 1844, a full third of all immigrants to America were from Ireland (during the Irish Potato Famine that number would swell to half of all immigrants), and prejudice against these easily-identified people was especially high. Business signs read, “Irish Need Not Apply.” Poverty redlined them into Irish ghettos. Few ever got out of the east coast cities where they’d landed. Given the huge proportion of Irish to “Native Americans” (the term some longer-established immigrants or native-born Americans called themselves) and the lack of available jobs, it’s not surprising that by the 1850s the Irish would account for more than half the crime and prisoners in New York City. But the population saw this as a specifically Irish problem – they were naturally dishonest, violent trouble-makers, drunks and whores.

The U.S. government and media made things worse.

Fake News

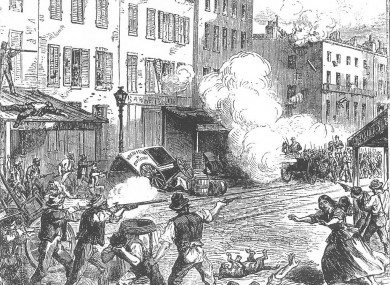

Early that year, a Philadelphia Bishop asked the school board to allow (mostly Irish) school children to read the Catholic Bible instead of the Protestant. The board agreed, but made it extremely complicated and so confusing that the board director later suggested to a flummoxed teacher that she slowly phase out all Bible study. Word got out and started a propaganda frenzy. In May, anti-Catholic newspapers in Philadelphia published stories that falsely accused Irishmen of robbing schools and stealing Bibles, which provoked a month of violent riots and attacks on Catholic churches. People were shot, rioters threw rocks, churches and books were set ablaze, the militia was called; and in June, a grand jury ultimately blamed the Irish and police for the whole thing, believing everything they’d read in the papers. The anti-immigrant rioters added the Mayor to the list, who’d been stoned (with rocks), the sheriff who arrived too late with nothing but clubs, and any other civil authority they could think of.

But it wasn’t over. In July, a priest heard a rumor that the “Native American” group was planning a parade, so he petitioned to arm the church with muskets to protect the church from destruction and looting. The day after the parade, thousands showed up at the church demanding the removal of the weapons. They refused to leave, so the sheriff mustered a posse. When that failed, he got more soldiers and a General. The crowd threw rocks. In response, the General ordered the soldiers to fire a cannon on the crowd. When a politician begged him not to do it, that man was arrested and detained at the church. The mob grew and brought their own cannon to “negotiate” the politician’s release. But once he was free, they attacked the church and smashed it up. Five thousand militia were called in. The mob attacked them with cannonfire, nails, chains, knives, and broken bottles. The July riots lasted seven days, and once again, a grand jury condemned the Irish. This became a divisive issue in the Presidential election, with parties pointing fingers at each other. And the violence prompted Philadelphia to fund their meagre police force with artillery, infantry, and a cavalry.

Meanwhile in Missouri, the Mormons were also a popular target of persecution at this time. A clash with Democrat President, Martin Van Buren, spurred the Mormon leader, Joseph Smith Jr., to switch political alliance and run for President as a Whig (more or less Republican). He intended to win his people full religious freedom and to offer America a “moral” candidate. His campaign barely lasted six months. A Missouri mob shot Smith’s brother in the face and then riddled Smith with bullets as he tried to leap out a window. All because an anti-Mormon article in the local newspaper accused Smith of polygamy and sedetion; and Smith retaliated by ordering its press machine destroyed. Perhaps a rebuttal instead of cancel culture would have ended the story differently. Five men were indicted in the killing but later acquitted by a jury. Does any of this sound vaguely familiar?

The Very Elect

In contrast, across the nation, people of the Millerite Movement fully anticipated that all these difficult questions of what to do in these uncertain times, would become moot with the imminent Second Coming of Christ. They were sure it would all be over in October, just before the election. We all know about the Great Disappointment. Some people--who’d given up all their belongings, were ridiculed, perhaps even disowned by family--lost all faith as a result. They gave up. Others, turned back to the Source and re-read their Bibles. They realized that they, not God, had made a mistake in interpreting scripture, and they were able to re-affirm their faith. The next few years saw them coming to a true understanding of Bible prophecy and doctrine.

It’s been said that those who’ve never questioned have never fully believed. Strife and disappointment may actually be a crucible to help your unbelief.

There are many lessons to take from the year 1844 about difficult times, political unrest, uncertainty and moral ambiguity, and I hope you’ll give it much more thought. But the most important lesson is that times of doubt are when we most need to connect with God, to return to His word for answers and reassurance. The Millerites who turned to God for truth and healing became the remnant church of the Seventh-day Adventists.

Whether or not you agree with the church, Christianity, or God—keep searching for answers. Pray, study, and come to your own conclusions. God doesn’t want blind faith from us. He invites us to “Come let us reason together” (Isaiah 1:18), permitting us the freedom to question in the hopes that we will seek Him and a deeper spirituality.

Sometimes, as with Job, the answers are beyond our understanding, if only to put our ego in check. God told Job, go ahead, ask your questions—and trust Me. God’s only requirement of us is to have an open heart, to sacrifice our pride, let go of our desire for control and omniscience, and offer Him our humble, receptive, broken spirit (Psalm 50:16-17). That is a heart He can work with, a heart able to trust and listen.